Is Median Income Really Stagnant?

By Matthew Benzmiller

We don’t really know.

“It’s the economy, stupid!” could have been a slogan for this election cycle too. Due to slow economic growth, the economy is one of the top issues debated during this election cycle. One statistic that has been tossed around by political pundits and politicians alike is that Americans haven’t had a pay raise in 16 years, represented by the falling median income in the United States since the late 90s to the early 2000s.

It’s a convenient sound bite for both sides. Republicans can point to it as a sign of a failure to revitalize the economy, and Democrats see it as a reason to raise the minimum wage or provide more welfare to those with low incomes.

However, economic figures can easily be used to further a certain group’s interest. It’s occasions like these that we should keep in mind the words of economist Henry Hazlitt:

Economics is haunted by more fallacies than any other study known to man. This is no accident…While certain public policies would in the long run benefit everybody, other policies would benefit one group only at the expense of all other groups. The group that would benefit by such policies, having such a direct interest in them, will argue for them plausibly and persistently. It will hire the best buyable minds to devote their whole time to presenting its case. And it will finally either convince the general public that its case is sound, or so befuddle it that clear thinking on the subject becomes next to impossible.

As Hazlitt says, all statistics should be taken with a grain of salt. In fact, there are several different ways to measure economic factors, such as inflation, that would result in different statistics and less harsh sounding one-liners for economically illiterate journalists and pundits to use.

An example of this is the current debate about stagnant wages. Dr. Don Boudreaux covered the subject in 2012 when the same issue was being debated. He outlined three considerations we should be taking into account when examining this issue: 1. How inflation is calculated, 2. the benefits workers are receiving other than wages, and 3. the distinction between statistics and individuals. He demonstrated the first point by showing that equally respected indexes can yield different results when comparing income.

Second, he argued that fringe benefits must be included when considering income, and that over time, those benefits have increased as a portion of income compared to in the past. Lastly, Dr. Boudreaux explained what he calls the most important point. He asserts that statistics can be misleading when they are applied to individuals. The only thing we can deduce from statistics about average wages using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to adjust for inflation, is that the average wage has decreased, but it does not take into account individuals included in those groups.

A changing work force can increase or decrease those statistics. If more people join the work force who earn on average a lower pay than those who have been employed longer, the average wage decreases, suggesting that everybody is worse off. But, people who were unemployed are better off, as they now earn income, and experienced workers may be earning more, even though the average is now lower.

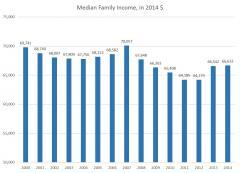

Dr. Mark Perry, an American Enterprise Institute scholar, agrees and explores demographic differences further in a macro-economic statistic. He says, “changing US household demographics and retirement trends can help explain the 7.2% decline in median household income from the peak of $57,843 in 1999 to $53,657 in 2014.” Dr. Perry’s three main points are that the number of dual income households have decreased while households with no income earners have increased, there has been an increase in retirees, and there has been a decline in the average number of hours worked per household.

He explains this discrepancy:

In fact, a linear regression model reveals that more than 90% of the decline in median household income between 1999 and 2014 can be explained by the decline in average household work hours, so there is a very strong statistical relationship between median household income and average household hours worked, as expected.

This sort of correlation should not be ignored when considering if wages have stagnated or not. Other scholars agree. For example, Dr. Jeffrey Dorfman pointed this out in his Real Clear Markets article, titled “The Obvious Reason for the Decline In Median Income.” He says, “It certainly makes sense that if households do not work as many hours, the earnings of those households may struggle to rise.”

This is not at all bad however, as Ryan McMaken, Editor of Mises Wire and The Austrian at the Mises Institute points out:

These factors can cause median incomes to decline, but don't necessarily suggest a stagnating or worsening economy…In other words, it could be that individual incomes are going up, even if household incomes are declining. Perry is correct that all of these factors could be contributing to a decline in household median wages, and that falling household wages are not necessarily evidence of a stagnating economy.

McMaken further explains why these figures are not necessarily signs of stagnation, but there are other factors we can examine from these findings to apply the economic outlook. He concludes that this only furthers the need for a firm commitment to economic theory:

This is why Ludwig von Mises referred to statistics and numerical analysis as "history" and not really as economics. Mises believed we can only determine causality using economics, which is a purely logical discipline based on core assumptions about human action. Quantitative analysis can help us figure out how to apply economic theory, but only good economics (in the Misesian sense) will tell us the direction of causation.

So, is medium income really stagnant? We don’t really know. However, considering the advice of Hazlitt and Mises and the opinions of the economists, it is best to be vigilant of those who would use opportune sound bites to sway you into thinking one policy is right, regardless of how convincing a statistic might sound at a glance.